The Normalisation of Racial Bias in SA’s Tech Startup Sector

Thirty years after the end of apartheid, against the backdrop of building an inclusive economy, you’d think that identifying a racial fault line in South Africa’s tech startup sector would be shocking news. Sadly, that’s not the case. The real kicker in this story is not that a racial fault line exists, but rather that it is accepted as normal.

Let’s look at what this demographic fault line looks like before getting into why it is accepted as normal.

While conducting PhD research, I examined the work of 120 startups—70 in Cape Town (CT) and 50 in Johannesburg (JHB)—launched between 2013 and 2018, as I was interested in understanding the digital economy as a manifestation of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). The 4IR was introduced as a theory of change by the influential World Economic Forum in 2016 and has since dominated the global digital policy agenda, including in South Africa (SA), entrenching a model of innovation steeped in neoliberalism. The 4IR has, in fact, become the putative definition of the digital economy in SA; people routinely refer to it when discussing the digital economy.

Thus, the significance of the periodization of my sample is that the origins of a startup sector steeped in neoliberal ideology has formed the basis of a digital economy that has expanded significantly over the past decade. During this time, the core characteristics of startups have remained unchanged.

The demographics of the South African tech startup sector

Upon examining the demographics of the startup founders in my sample, I discovered the existence of a significant racial fault line. A whopping 80% of the startups in my CT sample were launched by white South Africans. White men dominated the sample. The JHB sample was less extreme. However, more than half, i.e., 52% of the sample comprised of startups launched by white South Africans—again, with men dominating.

At 120 startups, my sample was huge, which gives it statistical power. And since CT and JHB are the main tech hubs in SA, this also means that these findings can be applied to an overview of the country’s digital economy as a whole.

Implications of racially skewed demographics in SA’s startup sector

So, what are the implications of this skewed racial demography and why is it a problem?

Firstly, in a majority-Black country, this finding has significant implications for the transformation of the economy, which remains a point of contention 30 years after apartheid. As the digital economy grows and permeates all aspects of economic activity, it adds another layer of complexity to the lack of transformation in SA’s economy.

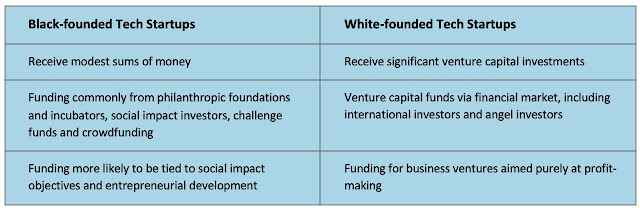

Secondly, my study found that white-founded startups received more investment funds than those founded by Black entrepreneurs. In addition, there was a qualitative difference between investments in white and Black founded startups.

|

| The qualitative difference in funding received by Black and white founded startups in South Africa (Source: Fazila Farouk) |

Meanwhile, the data also revealed a correlation between innovations with a focus on social inclusion and founders who were Black and/or women. For example, this demographic was more likely to develop digital innovations targeting the township economy or solutions aimed at supporting access to credit for the poor.

On the other hand, white startup founders operate in the capital market. These are the entrepreneurs with the real freedom to innovate because investment management is overwhelmingly dominated by white men—and white investors tend to prefer investing in startups run by white founders. This problem is not unique to SA. Researchers and analysts have identified this problem in other parts of Africa and the US, highlighting it as systemic.

The outcome in SA is that white startup founders receive massive amounts of funding from the financial market, including tens of millions in US dollars from international investors. Meanwhile, the financial market’s singular focus on profit-taking revealed itself in the data I gathered, showing a correlation between the dominance of white men in the tech ecosystem and the prevalence of extractive, rent-seeking digital innovations. In this regard, a respondent in my study simply described the core characteristic of tech startup founders in SA as “privileged white South Africans” trying to turn the money they have access to “into more money”.

This, of course, is considered perfectly normal and acceptable behaviour within a capitalist system. The problem, however, is that it results in the dominance of innovations that extract value from the economy with complete disregard for their contribution to economic inequality. If you’re interested in learning more about this phenomenon, an earlier article that I wrote bemoans the uninspiring and skewed nature of digital innovation in SA in the context of rampant financialization.

Rationalist theories that normalise racial bias in the startup sector

Returning to the issue of the rationalisation and normalisation of racial bias in SA's startup sector, the basis for this incongruity seems rooted in questions about whom we trust in business, particularly in relation to whom we trust with our money.

I attended more than one startup event where the host advised entrepreneurs in search of investments to network along racial (and/or gender) lines. To paraphrase, they would unashamedly advise: "If you’re white, network with white people. If you’re Black, network with Black people. If you’re a woman, network with other women".

This offensive advice is entrenched in mainstream business school behavioural theories that emphasise social, cultural, and ethnic similarities between people as objective criteria for establishing trust.

For example, in identity theory, interaction biases are based on similarities in the personal traits of individuals involved in the investor-entrepreneur relationship. Identity theorists elevate the issue of identity alignment in the high-risk investment environment, arguing that people feel more comfortable collaborating with partners they can identify with culturally and/or ethnically. On the other hand, agency theory identifies personal networks as the solution to difficulties caused by information asymmetries between investors and entrepreneurs. In this respect, who you know matters because social networks provide the channels that enable the flow of personal information in financial markets.

Both of these theories highlight social, cultural, and ethnic similarities within social networks as objective criteria for establishing trust. However, this narrow focus on actors within networks obscures how these networks function to exclude certain groups by controlling access through network protocols, thereby neglecting questions about power. In a racially stratified society like SA, this is not just problematic but also irresponsible due to its indifference to power dynamics, unwitting promotion of racial bias, and inattention to inequality.

Because mainstream behavioural theories are based on rationalistic epistemologies that lack historical context, we find ourselves in the disturbing situation where trust is tied to racial similarity in the startup sector. This was an uncomfortable discovery for me. It’s not that I didn’t expect to find a racial hierarchy in SA’s startup sector—it’s that I didn’t expect to hear people openly promoting racially defined relationships as rational and normal. To say the least, it was extremely jarring.

Understanding the demographics of the digital economy through theories that critique capitalism

In contrast to the aforementioned behavioural theories, the sociologist Manuel Castells offers a strident critique of capitalism that recognises the power of networks in the digital economy. Castells describes informational capitalism (capitalism driven by information technologies) as the most voracious form of capitalism. He identifies the financial market as the most powerful network in the global economy. His description of how financial and non-financial elites function as a culturally cohesive and internationally mobile group connected via alumni and social networks within informational capitalism is instructive in illustrating the linkages that connect (white) investors from the Global North to (white) entrepreneurs from the Global South.

However, Castells is not a race theorist, and in a country like SA, racial analysis simply can’t be excluded. Building a bridge between his analysis and critical race theory enables an understanding of how money continues to flow within the white demographic in the tech ecosystem.

For example, Eduardo Bonilla-Silva’s theory of racial praxis helps assign a racial identity to investors and entrepreneurs through its structuralist and materialist interpretation of racism, arguing that different racial groups receive different rewards based on the positions they occupy in racially stratified societies. Bonilla-Silva does not attribute racism to supremacist ideology but to racial praxis, which he describes as ‘racialised social practices’ that develop as a social structure to preserve the advantages of a dominant racial group, motivated by a particular ideology (e.g., capitalism). Consequently, for Bonilla-Silva, “racism is not (about) the ideas that individuals may have about others, but (about) the social edifice erected over racial inequality”. This results in rewards accruing to the dominant racial group as resources circulate within it.

From this vantage point, the racial hierarchy that manifests in the tech ecosystem is illustrative of racial praxis as the transfer of capital between white men as members of a dominant racial group at the apex of the South African economy.

And while Bonilla-Silva’s racial praxis shows how racial domination functions as a practice in racially stratified societies, Dolores Calderón highlights ‘whiteness’ as a concept embedded in the rationality of capitalist ideology.

Calderón’s conceptualisation of the ‘epistemic nature of whiteness’ as a ‘flat rationality’ refers to ‘whiteness’ as a pre-ontological way of knowing that is articulated as common-sense truth, and organised both hierarchically and unidirectionally. Calderón frames the ‘flat epistemology of whiteness’ as a capitalist sensibility within the establishment. Drawing on Herbert Marcusé’s theory of technological rationality, she highlights the one-directional nature of capitalist relations, demonstrating how the demands of capitalist reproduction flow exclusively from the white establishment carrying with it certain requirements.

Accordingly, the skewed racial outcomes in the tech ecosystem can be viewed as a problem rooted in capitalist ideology. Calderón depicts this as a form of colourblind discrimination that reproduces racial inequality as the consequence of a pre-ontological sensibility rooted in rationalist thinking that privileges white excellence. For example, this deeply embedded sensibility has driven Black Kenyan tech entrepreneurs to employ white staff to front their startups, as an acceptable practice to improve their chances of attracting investment funds. It’s not that these white staff members have superior talents; it’s that Black entrepreneurs have devised a solution to navigate a racist capitalist system.

Discriminatory practices prevail

To conclude, despite evidence of exclusionary elite networks, social organisation that gatekeeps wealth within dominant groups, and a capitalist rationale that privileges white excellence, we continue to be misled by mainstream behavioural theories that reproduce racial inequality. These theories continue to dominate thinking in the tech sector’s investor-entrepreneur ecosystem, where, despite embodying discriminatory practices, racially defined dealings are considered rational within the scope of capitalist relations. In other words, racially skewed outcomes in the startup sector are simply viewed as a form of market failure resulting from rational behaviour that does not produce balanced outcomes. Meanwhile, the factors driving these unequal outcomes are glossed over and remain unaddressed.